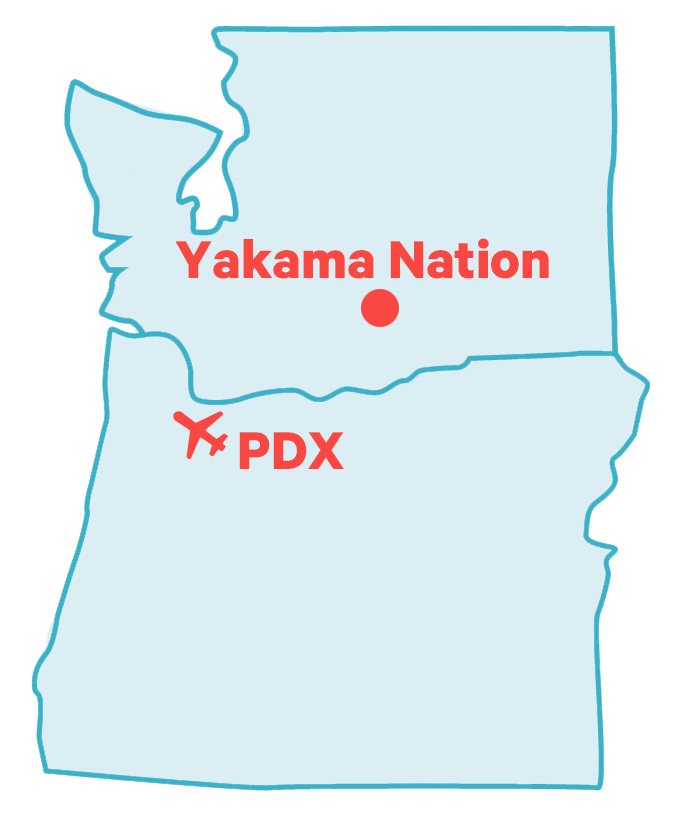

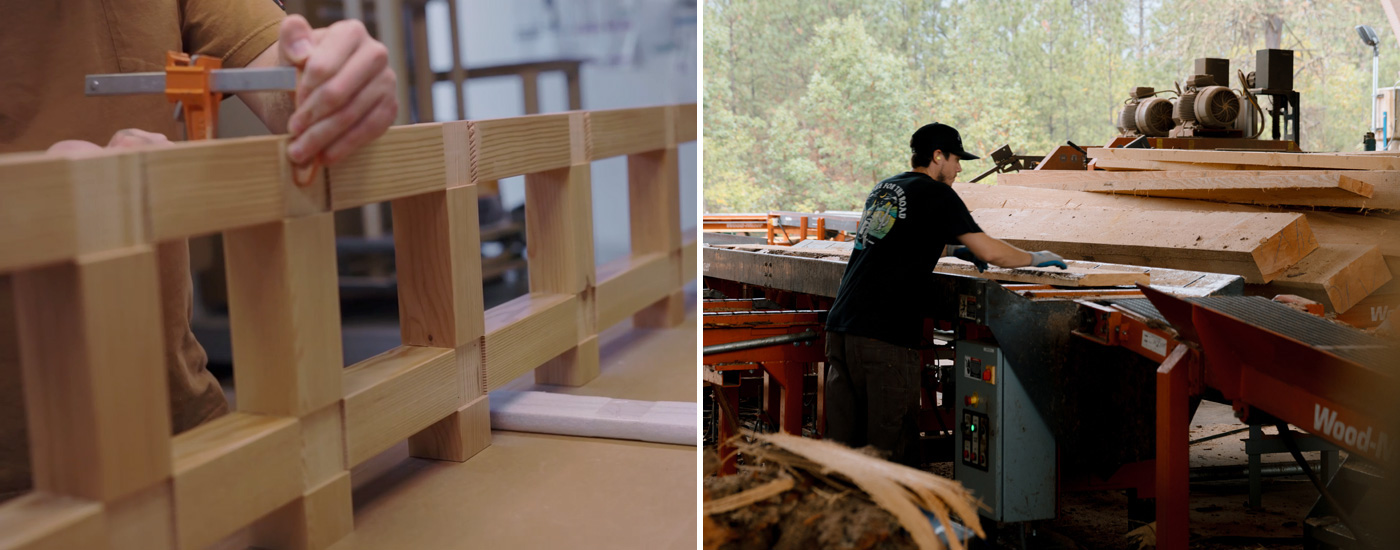

When PDX built the nine-acre roof for our main terminal out of local Douglas fir, we wanted every square inch to represent the people and places of the Pacific Northwest.

That's why we built partnerships with four tribes in Oregon and Washington: The Yakama Nation, the Coquille Indian Tribe, the Skokomish Indian Tribe, and the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians. All four harvested the timber they supplied to PDX from their sovereign lands.

When you're finally able to visit the main terminal, starting this fall, you'll see the results of this partnership in the building’s curvy laminated beams, ceiling lattice, and wooden shops.

We asked representatives from our four tribal partners to tell us the story of the wood and the forests it came from. Here is what they wanted you to know.

Special thanks to Sustainable Northwest and Sustainable Northwest Wood for helping us forge these important partnerships.

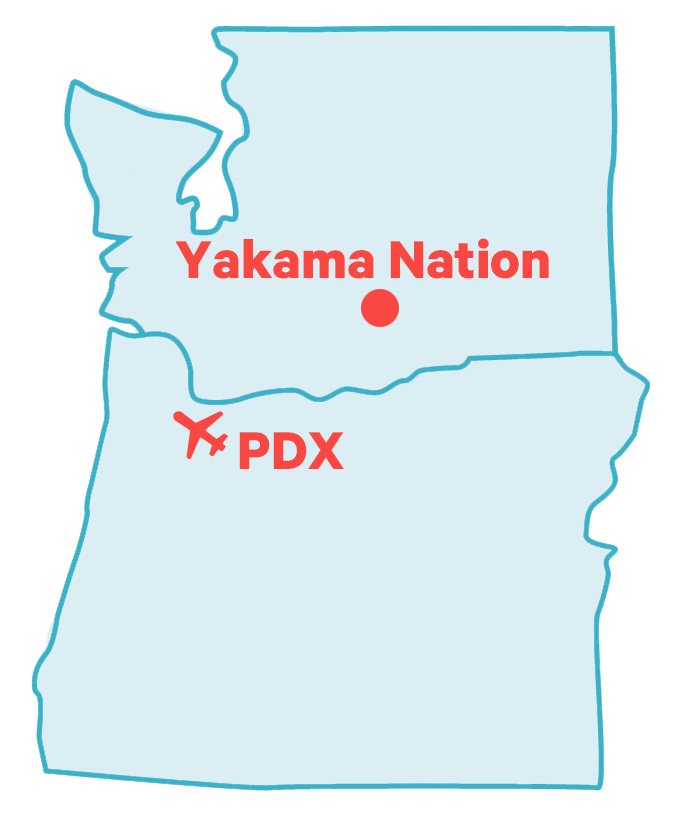

Yakama Nation

Cristy Fiander, Resource Manager, Yakama Forest Products:

Yakama Forest Products is an enterprise of the Yakama Nation. All the wood we supplied to PDX came from the Yakama Nation Reservation, and the timber was milled at our own mill. Our reservation is 1.3 million acres, and 480,000 acres is a commercially harvested forest. These trees, and the lumber we produce, are truly a gift from our Creator.

Yakama Forest Products is an enterprise of the Yakama Nation. All the wood we supplied to PDX came from the Yakama Nation Reservation, and the timber was milled at our own mill. Our reservation is 1.3 million acres, and 480,000 acres is a commercially harvested forest. These trees, and the lumber we produce, are truly a gift from our Creator.

Our tribe is very proud of the way we manage our forest. The only reason our forests are certified by the Sustainable Forestry Initiative is to show purchasers that we're logging sustainably. But those SFI requirements? We have our own standards set forth by our ancestors that meet and exceed them.

“I want people to know that the Yakama people and our ancestors are from this area. And we are still here.”

—Cristy Fiander

We manage our land in a way that mimics fire: We log for forest health by taking out weaker trees. If the forest grows too thick and overstocked, diseases come in such as root rot, bugs, or needle blight. We harvest them before mortality sets in to continue to store carbon as lumber products are made. We always leave the best trees, the ones with the best crowns, the ones in the best health that will in turn produce healthy natural regeneration. We also manage the land for our foods and medicines. When we take people up there to see our forests, we get so many compliments, people saying we have the best forests in the world.

I want people to know that the Yakama people and our ancestors are from this area. And we are still here and active. Our usual and accustomed areas for trade, travel, fishing, hunting and gathering extend down to Portland and all the way to the ocean. By showcasing our lumber as far south as Portland, we are also showing that we're contributing to the Northwest in many different ways.

Skokomish Indian Tribe

Tom Strong, CEO, Skokomish Indian Tribe, and vice chair, Skokomish Tribal Council:

After the Cobell Settlement of 2009, our tribe began to buy back alienated and fractionated reservation lands. And after a separate settlement with Tacoma

Public Utilities returned forest lands to the Skokomish people, we realized that we had timberlands that required attention. We wanted to manage our

resources to their highest and best purpose, as determined by the Skokomish tribal government. So we developed a forest management plan by working with

Northwest Natural Resource Group. The Douglas fir timber that went to PDX was selectively thinned from 143 acres of overstocked forests.

After the Cobell Settlement of 2009, our tribe began to buy back alienated and fractionated reservation lands. And after a separate settlement with Tacoma

Public Utilities returned forest lands to the Skokomish people, we realized that we had timberlands that required attention. We wanted to manage our

resources to their highest and best purpose, as determined by the Skokomish tribal government. So we developed a forest management plan by working with

Northwest Natural Resource Group. The Douglas fir timber that went to PDX was selectively thinned from 143 acres of overstocked forests.

“Our forest management plan is a continuation of who we are as a people.”

—Tom Strong

Ultimately, we are the stewards of the land. We've all come to understand the impacts of human-caused development in our area. We've seen the impacts from failing septic systems affect our shellfish beds. We see the impacts of climate change with ocean acidification. We're watching these things happen around us. It's imperative to us to do what we can to mitigate those effects. We have people out there right now fishing for shrimp. We want to see those things continue. We have people working the beaches. We want to see those recover.

The Skokomish Tribe is a tribe steeped in its culture and its history. We've been trading, tribe to tribe, to Oregon and beyond for generations. This timber is part of our tradition of trade and commerce. Our forest management plan is a continuation of who we are as a people. We're a giving people, and we try to support and improve outcomes for everybody.

That's what I would hope people would know. We were created here. We will be here forever. And we want to ensure the things we enjoy, and the lives we have enjoyed forever, is something other have as well.

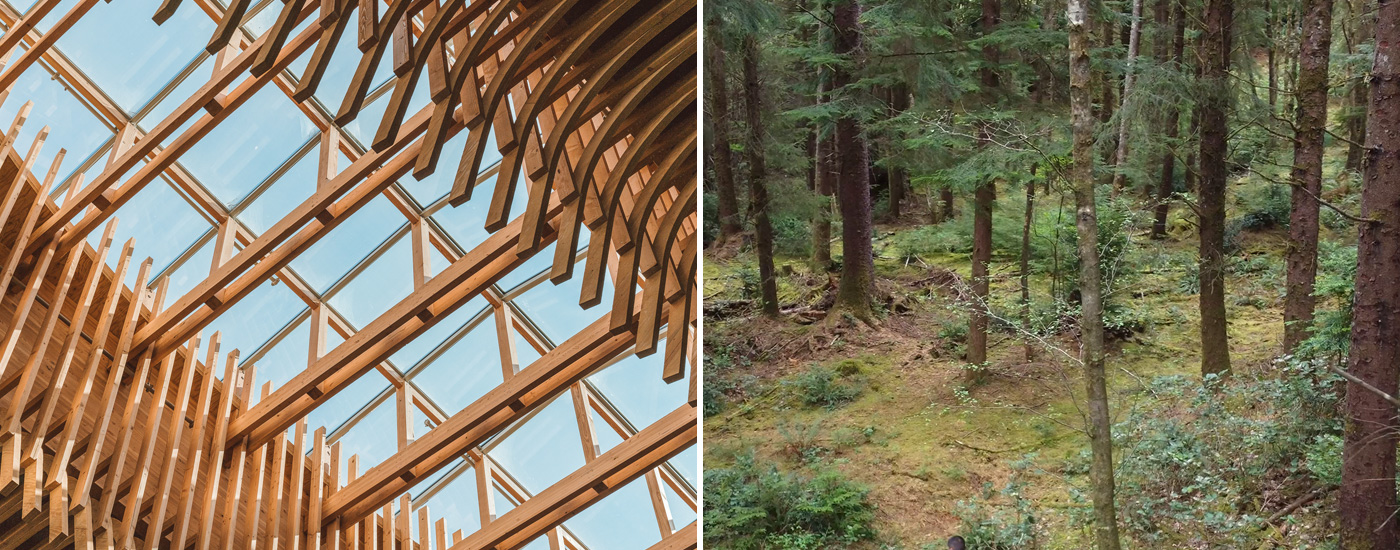

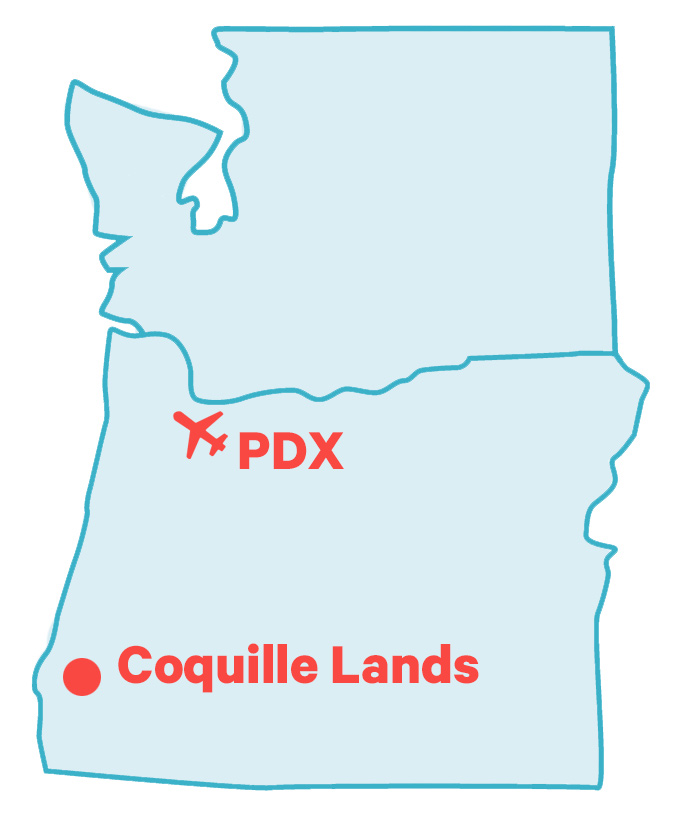

Coquille Indian Tribe

Brenda Meade, Chairman, Coquille Indian Tribe:

Just like the red cedar and Douglas fir that inhabit our coastal forests, the Coquille Tribe is tremendously resilient and adaptive. We have survived

epidemics, forced removal, massacres and the utter dispossession of our lands and resources. In 1954 Congress passed a law terminating our federal

recognition. Termination was devastating for our people. Our government no longer considered us to be indigenous.

Just like the red cedar and Douglas fir that inhabit our coastal forests, the Coquille Tribe is tremendously resilient and adaptive. We have survived

epidemics, forced removal, massacres and the utter dispossession of our lands and resources. In 1954 Congress passed a law terminating our federal

recognition. Termination was devastating for our people. Our government no longer considered us to be indigenous.

In 1989, Congress recognized its grave error and passed the Coquille Restoration Act. Seven years later, it returned 5,400 acres of our ancestral forest lands to us. Later, we purchased another 3,200 acres of ancestral homelands on the Sixes River.

“It's not about selling a product or making money. It's about making sure that our next generations have more than what we have.”

—Brenda Meade

In 2019, we became the first tribe in the nation to assume nearly full control of our own forest management. As a result, we now manage our lands under our own tribal laws and land management criteria, free from the remnants of the earlier paternalistic federal land management regime. Today, we focus on holistic management and correcting the industrial timber mess that happened on those lands.

This land has always provided everything we need, and as long as we're good stewards, and take care of those resources with our traditional knowledge, we can have a sustainable forest that's healthy. These are our ancestral homelands, and we will always be here to care for them. These lands provide our traditional foods, basketry materials, and materials for our ceremonial gatherings. It's not about selling a product or making money. It's about making sure that our next generations have more than what we have, that it's better for them than it was for this generation.

I'm really proud of the fact that people visiting Portland will see a bit of Oregon's culture in the airport. It's so important to our Coquille potlatch culture to welcome our guests. This is an opportunity to do that.

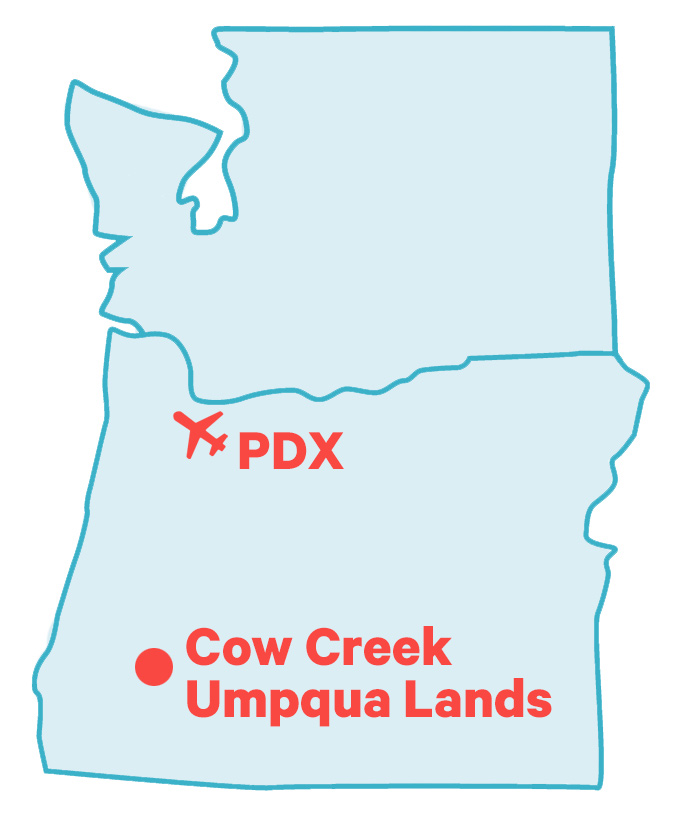

Cow Creek Band of

Umpqua Tribe of Indians

Carla Keene, Chairman, Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians:

In 2018, the Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act honored our 1853 treaty and restored 17,000 acres of our ancestral land to us. Then, in 2019, the Milepost

97 Fire destroyed 3,634 acres of our property — 20 percent of what we were just given back. When I first went up there, it looked like an atomic bomb had

gone off. It was devastating to see.

In 2018, the Western Oregon Tribal Fairness Act honored our 1853 treaty and restored 17,000 acres of our ancestral land to us. Then, in 2019, the Milepost

97 Fire destroyed 3,634 acres of our property — 20 percent of what we were just given back. When I first went up there, it looked like an atomic bomb had

gone off. It was devastating to see.

The reason that the wildfire burned so hot, and why we could not get to it quickly enough, was because the forest had not been taken care of. So we started cleaning the land. We found small logs that were still salvageable and brought them out. We build a small mill to process the wood. That's the wood that went to PDX.

“Conservation is about management. Everything that's living and breathing, you have to take care of it.”

—Carla Keene

We've now replanted the land that burned. It has one million new trees on it now. We're always going to have wildfires, but if we keep the land clean - thinning the trees, cleaning the forest floor - there will be minimal damage.

If you go back today, you will see new seedlings and new roads. You see hope for the future. What we have now is a legacy for our seven generations, to show them what can happen: Even though something bad happened, something good came out of that.

Conservation is about management. Everything that's living and breathing, you have to take care of it. It gives back if you take care of it. That's what our ancestors did, and it's what I believe that we're doing.

Photo credits:

Aedin Powell Media,

Anvil Northwest,

Dawn Jones Redstone,

Hannah Letinich