Talisa Shevavesh of architecture firm ZGF works in her studio on models of new airport designs.

Talisa Shevavesh of architecture firm ZGF works in her studio on models of new airport designs.

Quick update: This article was written in 2020. The new PDX is here! Want to meet it?

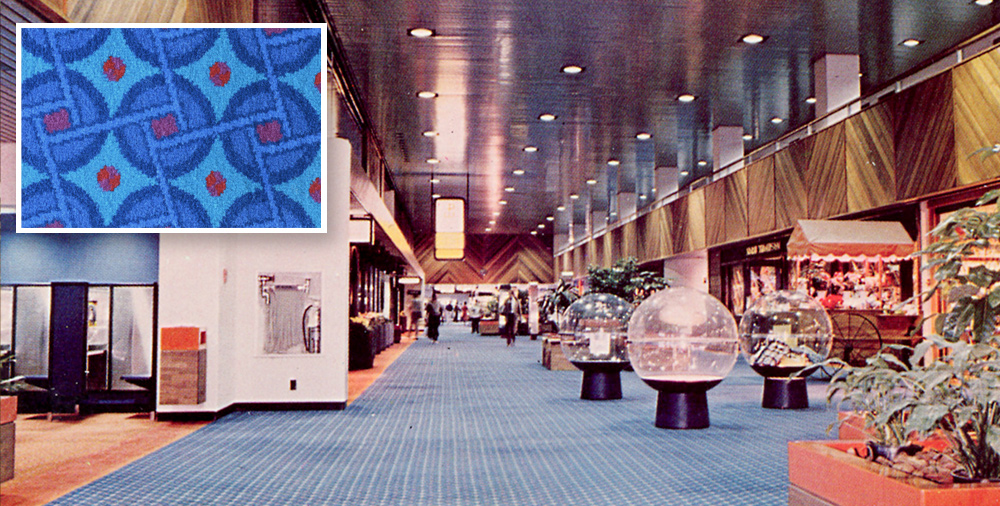

If you were designing an airport several decades ago, physical models would've been your primary tool for visualizing the structure before building it in real life. These days, more and more architects rely on computer renderings and digital 3D tools. As a consequence, model making is becoming a somewhat rare craft.

But there are still plenty of leading architects who regard the tactility of making something by hand as crucial to their process. Count partner Gene Sandoval and the award-winning team at ZGF among them. The architects behind the fresh PDX designs have relied on a series of physical models, as they fine-tune plans for the new main terminal inspired by the craftsmanship and heritage of our region.

The model is a helpful visualization tool for the architects and builders bringing the project to life.

The model is a helpful visualization tool for the architects and builders bringing the project to life.

Those models are largely the handiwork of second-generation model maker Talisa Shevavesh — along with numerous design teams, high-tech machining equipment and even a few model-making robots. The largest and latest model of the terminal is perhaps the most extraordinary, measuring 20 by 30 feet with the woven wooden roof spanning an interior filled with “greenery” and plastic “travelers.” It was the perfect pandemic project for Talisa and her team, as it took months of painstaking work to design and build PDX in miniature.

We sat down with Talisa and Gene (via video chat, of course) to discuss the ins and outs of physically building, and rebuilding, the massive model; how the process influences their design decisions; and how one becomes a model maker in the first place.

The model of the airport's new main terminal is beautiful on its own. (Check out the model pictures.) How does the creation of a physical model like this influence the design process?

Gene: Physical models have been around since the advent of our profession. It's a way for us to truly see how things are put together. They come in different scales, materials and levels of detail according to where you are in the process of a project.

Recently, with the focus on computers, there's this kind of detachment from the materiality of the work. For PDX, we immediately knew we wanted to use physical models. We wanted to go back to the whole idea of making by hand, especially since the new main terminal prominently incorporates wood and natural elements.

We wanted to make sure that we were using our hands and letting the material tell us what it wants to be. And I think that's a significant reason why the model is worth it because it was really using our hands and letting the wood tell us the form and the resolution that it naturally is akin to.

ZGF partners Sharron van der Meulen and Gene Sandoval, right, take inspiration from the region's natural landscapes and cultural heritage.

ZGF partners Sharron van der Meulen and Gene Sandoval, right, take inspiration from the region's natural landscapes and cultural heritage.

Talisa, can you give us a crash course in building a model like this? Walk us through your process.

Talisa: The new main terminal has been a bit of a different process than most of our projects because we've built so many models as the design evolved. You could say this started four years ago when the project was more in its infancy when I was working closely with our design sub-teams to figure out smaller pieces of the architecture like roof pieces and windows. At the beginning of 2020, we wanted to see everything put together, so we started building this much larger model. It was just a matter of choosing how much of the building we wanted to build and at what scale. Ours is done at a half-inch scale — each half-inch equaling one foot — making this the largest model of the project at 20 by 30 feet.

What does a day in the life of a model maker look like for you?

Talisa: Beautiful chaos most times. [laughter] But I think a typical day with this team starts with some kind of model that we've been developing that we then take to our design teams to review together. A lot of the time I get the comment, “It doesn't look like I thought it would, having looked at it on the computer.” It's a lot of back and forth, switching elements out and building additional pieces to add onto it. My role is to help the designers visualize their thoughts and make the right decisions.

When it comes to assembling a large model like this one, what is the actual construction process like?

Talisa: This model is more on the sophisticated side of model building, as we lean heavily on digital fabrication. We bring in robots to make sure that the pieces are cut precisely. The model gets built in the computer first to make sure all of our parts are going to align the way that we were expecting them to, then we “hand it off” to the machine and the machine operator to cut it out. After that, we'll bring the different pieces to glue, nail and screw them together.

After studying architecture, Talisa followed her parents into making models, a challenging and technical craft.

After studying architecture, Talisa followed her parents into making models, a challenging and technical craft.

Is it fair to say you're a second-generation model maker? And how do people react when they learn what you do for a living?

Talisa: Both of my parents built models when I was ... well, I guess they still build models. That was their main profession when I was a little kid. And when I got into high school, I started working at their studio and got into it in that back-end, roundabout way. I went through architecture school because my interest was sparked by building models for architects.

It is very niche in this day and age. A lot of people ask me, “Aren't computer renderings just as good these days?” That's the big curiosity because the video game industry has gotten so advanced and architectural renderings have followed really closely.

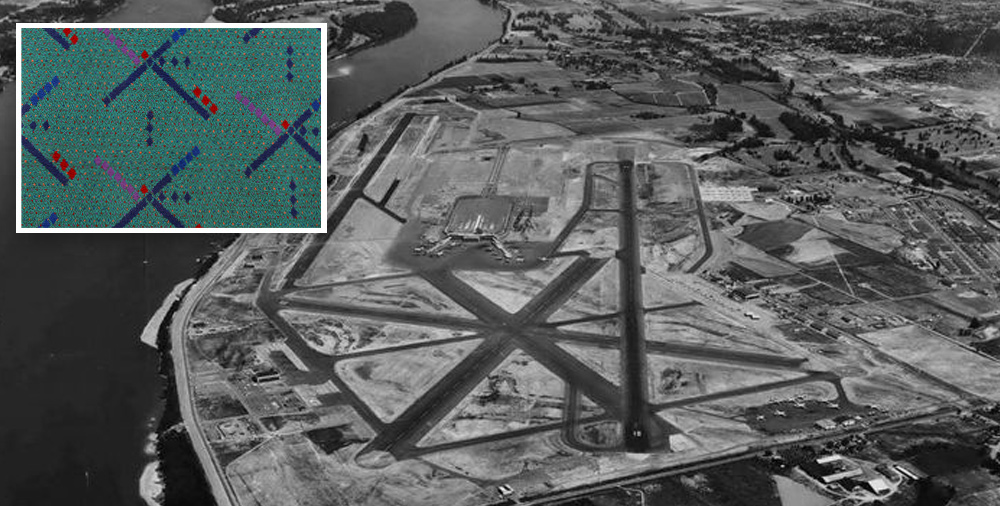

Gene, I've heard that you have a long history of working with the Portland International Airport. What does this project really mean to you?

Gene: I've been working as an architect with the airport since probably 1994. Having moved here from another country, the airport's my gateway to a different civilization so to speak. A different culture. It's a great honor and privilege to actually design what that gateway is — and one that represents who we are as a country, as a state and as a group of people. It's personal.

What happens to the model once the airport is built?

Gene: The model is going to get used by all the construction consultants to see what they're doing. Eventually, we hope to display it where the public will see it up close, so they can get an introduction to the original designs.

Talisa, as a model maker, why is a project like this so important to you?

Talisa: I want to highlight how delightful it is to have models as part of the architectural process. Personally, I have not seen models so involved in architecture’s day-to-day work, so to have a project that's so technology-heavy — so much of the roof is generated with computer algorithms — but to come back and verify it with something more craftsman and artisanal as part of the process, I think that’s really special.